The narrow lanes of Budgam are buzzing again flags fluttering, loudspeakers echoing, and candidates walking door to door, their words carefully crafted to touch both hearts and beliefs. But this time, the campaign doesn’t just carry promises of roads, jobs, or development it carries the weight of faith.

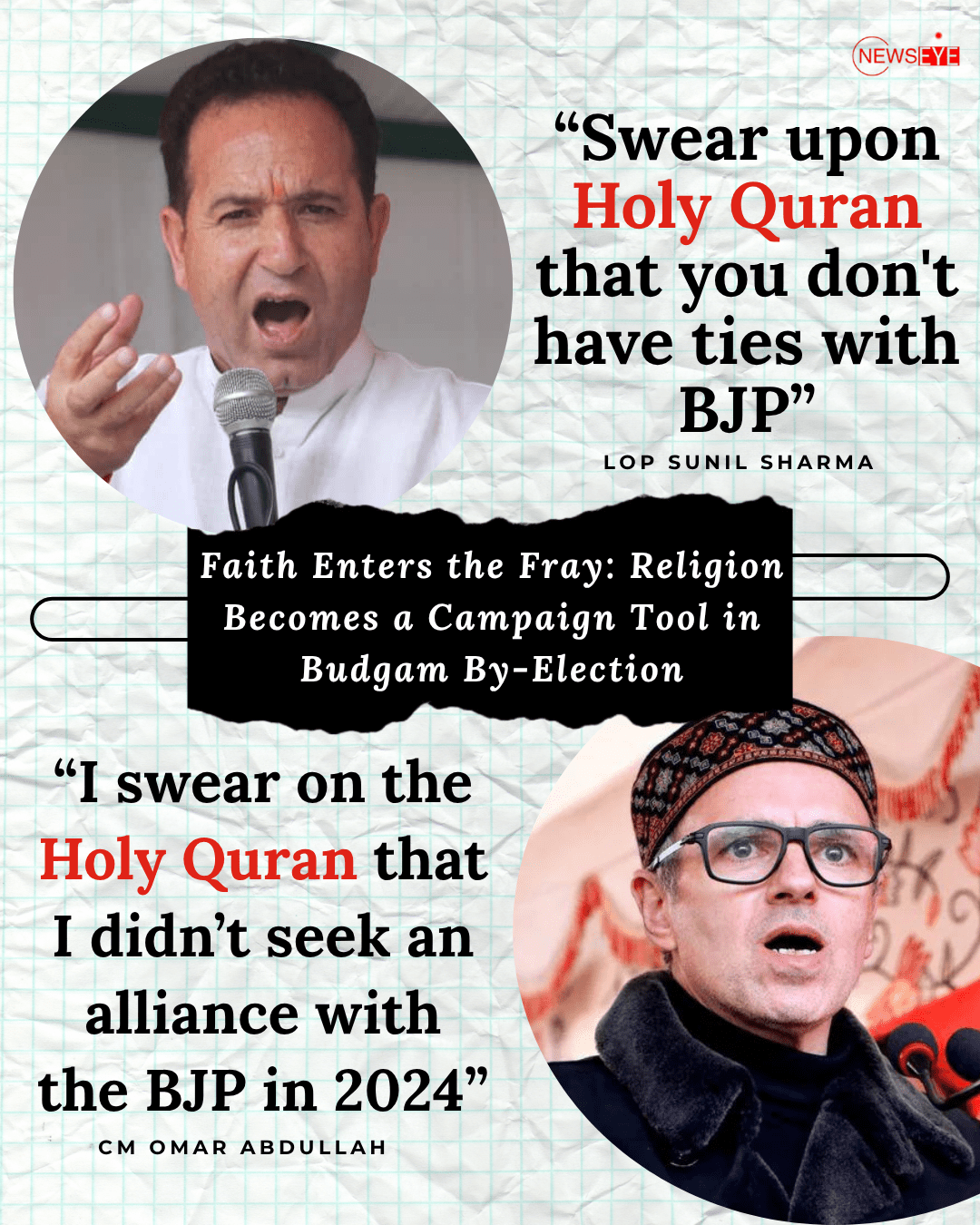

In one such rally, amid the autumn chill, BJP leader Sunil Sharma took the microphone and threw a challenge “If Omar Abdullah has no ties with the BJP,” he said, “let him swear upon the Quran.” The crowd fell silent for a moment, then murmurs rippled through the audience some astonished, others approving. Religion, once a quiet undercurrent in political speech, had suddenly taken center stage.

Hours later, Omar Abdullah responded. On X, his post appeared simply yet powerfully: “I swear on the Holy Quran that I didn’t seek an alliance with the BJP in 2024 for Statehood or for any other reason. Unlike Sunil Sharma I don’t tell lies for a living.” The message spread like wildfire through Budgam’s villages and marketplaces. In tea stalls and living rooms, people debated not the usual campaign rhetoric, but the meaning of that oath. Some said Omar’s act showed integrity; others felt uneasy that something as sacred as the Quran was being drawn into a political contest.

For decades, Kashmir’s politics has carried shades of faith it’s inseparable from the people’s identity, their sense of belonging. But in Budgam’s by-election, the blending feels sharper, more deliberate. Candidates seem to know that invoking faith can bridge emotional gaps faster than policy speeches. A verse, a symbol, or a sworn word can turn suspicion into trust, distance into connection.

Yet beneath the applause and emotion lies an uncomfortable truth when religion becomes a campaign tool, politics changes its language. Debates about unemployment, education, and governance fade behind vows of moral purity. The conversation becomes less about what leaders will do for the people, and more about how sincerely they believe.

Walking through Budgam’s streets, one can hear the tension in people’s voices. “He swore on the Quran,” one man says at a tea shop. “That must mean he’s telling the truth.” Another replies quietly, “Faith should be between a person and God, not between a politician and a voter.”

The by-election has thus turned into something larger than a local political battle it’s a test of where the line lies between personal belief and public persuasion. And as the campaign nears its end, one question lingers in the air of Budgam: should religion be the language of politics, or should politics finally learn to speak the language of action?